Fibre future: New techniques connecting more homes sooner

Broadband is key to future proofing our data needs. With only 3% of UK homes receiving access to full-fibre broadband services (FTTP), there is a sense of urgency for fibre infrastructure to be rolled out. In the past, FTTP has been hindered by the expense associated with widely delivering the service. However, in July, the UK government unveiled a £400m fund aimed at boosting fibre infrastructure to homes. In addition, Openreach, the body that runs the UK's fibre network, now suggest that new techniques could mean 10 million homes could receive super-fast fibre broadband by 2025.

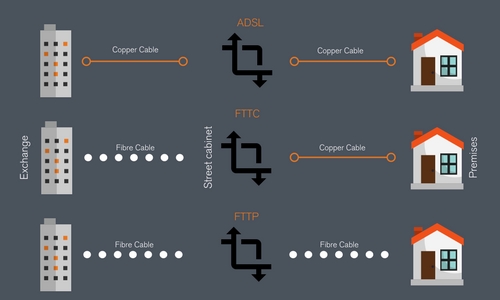

FTTP is generally regarded as the best broadband delivery service, and does not rely on slower copper-based connections to join local street cabinets to the home like the usual copper hybrid method does (FTTC). It is also more stable, efficient and reliable, with predictable speeds and fewer faults for customers. But what does going full-fibre mean, and why is it important?

In the past, our internet access relied upon the copper telephone network, connecting all the way from the exchange to your home. While copper is an excellent conductor for electricity, fibre optic cables are more suited to carrying data at high speeds. The most common method used in the UK today that currently supplies most of the population is FTTC – fibre-to-the-cabinet – which means fibre optic cable connects the exchange to the cabinet on your street, and then copper telephone cable carries your data the rest of the way. FTTP is thought to be the ultimate solution, where fibre cable carries your data from the exchange all the way to your home. The exception to these set-ups is Virgin Media, who use data-friendly coaxial cable for the cabinet to home transfer to achieve faster speeds than FTTC, but not as fast as FTTP.

But Openreach have suggested a new technique, called G.fast, which will be able to provide fast internet speeds by piggy-backing off the existing copper cable network. Tapping into the existing network means the work can be done faster and at less cost, Openreach suggest this new technique could halve the cost of delivering full fibre. At this stage, G.fast is only available in 20 locations, but the downside to the service is that it can become degraded in wet weather.

The government has formally launched a £400m fund to boost investment in FTTP broadband, but Openreach have called for a collaboration to assess if there is sufficient demand to justify the rollout. While most households and organisations do not currently need the potential 1Gbps speeds that FTTP can offer, the idea is to future-proof. As our data consumption continues to grow, safeguarding the infrastructure for a 21st-Century network capable of handling our future needs looks more and more necessary.